By J. Douglas Willms, President of The Learning Bar Inc.

On World Teachers Day, this blog presents an assessment framework, called Education Prosperity, that can be used to track the success of teachers, families, communities and public institutions in developing children’s cognitive skills and their social, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being.

As the president of the International Academy of Education, I am often invited to share ideas about school reforms. During a recent trip to Latin America, I found myself in a discussion focused on classroom improvements as a way to boost PISA scores. The conversation was illuminating, because the policymakers in that room—like so many others around the globe— had the best of intentions, but were nevertheless stuck in a model that had them looking in the wrong places.

As I told the group, the foundations for learning are established years before students sit down for the PISA exam or even enter a classroom. In a country that suffers from maternal and child malnutrition, where that particular meeting had taken place, understanding the ways that achievements in education are interconnected—and cumulative— is key to making policy changes that ensure our children are thriving.

These interactions form the basis of my new paper published by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), Learning Divides: Using Data to Inform Educational Policy. As the international education community prepares for the upcoming meeting of the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (17-18 October in Hamburg), understanding the interconnectedness of children’s learning processes is critical to measuring progress towards key SDG 4 targets.

Understanding and using data to inform policy

Despite our best attempts, students’ reading skills have not improved over the past fifteen years and if we are to move forward and make real progress, we need a better way of understanding data to inform policy. Indeed, ahead of the GAML meeting, we need to be advocating for a comprehensive and holistic framework—what I call “educational prosperity”— that acknowledges the importance of the foundations for successful learning. Our framework increasingly needs to embrace a life-course approach that considers the impacts of various processes from conception through late adolescence—and we need to be using these data to craft more effective policies.

Traditional approaches to measuring education progress have proven to be insufficient and are failing to capture a critical nuance: Looking at exam results for 15-year-olds—or even 10-year-olds— is misleading. Many of the existing frameworks have misled policymakers for decades because they ignore the cumulative result of a number of factors that affect children’s development. As researchers would put it, we’re using test results to make causal claims and while assessment is critical, it only captures the reality of a specific moment in time, rather than the cumulative and foundational factors that led up to it. Poor reading results in fourth grade, for example, are often the result of poor foundational support for literacy in the early years—and so may be an indication of misguided early childhood development policy or insufficient family support and not necessarily school policy, poor infrastructure, or low teaching quality.

An alternative approach through the education prosperity framework

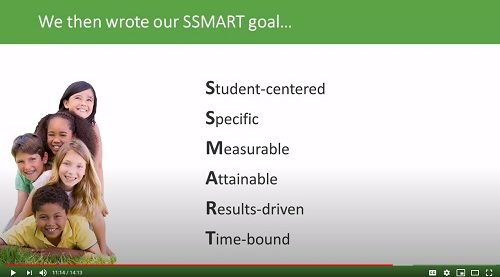

The “educational prosperity” framework presented in the new UIS papers offers an important alternative that can use existing monitoring data to track the success of families, communities and public institutions in developing children’s cognitive skills, as well as their social, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being. The framework provides a multi-dimensional understanding of development at each stage that looks at the role of families, institutions and communities. These ‘Foundations for Success,’ which drive outcomes along six stages of development, provide an important visualization of the ways that success can be cumulative and non-linear.

For example, prosperity outcomes for children in early primary school may include literacy and numeracy, but success is not dependent on institutional factors such as quality instruction and adequate learning materials alone. Rather, the framework operates under the understanding that success is also built on family factors such as parenting skills and family involvement, as well as community factors such as adequate resources and social capital. The framework uses a wider lens for understanding student outcomes—recognizing the reality that school factors and inputs alone are not the sole foundations for student achievement.

Focus on early reading

The educational prosperity framework is based on three interconnected premises. The first is that early reading needs to be the primary focus of educational monitoring systems. The reason is simple: literacy is a pre-requisite for later success in lower and upper secondary levels and provides the scaffolding for developing so many other skills, including numeracy, problem solving and socio-emotional know-how. Indeed, a failure to develop strong skills during the early years increases the risk of school failure.

Second, to better capture ‘school effects’, we can build an informative educational monitoring systems which incorporate the findings of over twenty years of research on the causal factors that lead to better student outcomes.

Third, results from the international studies need to be coupled with national studies and small controlled experimental studies, which can provide educational administrators with information for setting achievable goals, allocating resources, and creating policies for change. We don’t need to keep gathering data on things we already know and instead, should focus on the small-scale testing of reform and studies that focus on a small number of factors. We need to be measuring these in greater detail while tracking them longitudinally.

To be clear, I am not calling for the abandonment of large-scale international studies. Much of my research is based on PISA data, which has played a critical role in helping countries understand how well their students compare with students in other countries while generating the political will for investing in education. But it’s time to look beyond the international studies and consider additional ways to measure and guide our educational policies.

As countries decide to join cross-national assessments or continue to develop their own, I am hopeful that the “educational prosperity” framework will be an essential guide for individual countries—and the global community as a whole—to craft effective strategies that promote educational opportunity for all children.